|

Ford Motor Company Assembly Plant /

Quartermaster Depot /Charlotte Army Missile Plant

|

|

|

1. Name and location of the property: The

property known alternatively as the Ford Motor Company Assembly Plant,

Army Quartermaster Depot, and Charlotte Army Missile Plant is located

at 1776 Statesville Ave., 1101 Woodward Ave., 901 Woodward Ave., and

1701 Graham Street.

2. Name, address and

telephone number of the present owners of the property: The

owners of the properties are:

|

1776 Statesville Avenue

Parcel Id# 07903105

Eckerd of North Carolina, Inc.

PO Box 4689

Clearwater, FL 33518

|

1776 Statesville Avenue

Parcel Id# 07903102

Bancroft Realty Co.

PO Box 4689

Clearwater, FL 34618

|

1101 Woodward Avenue

Parcel Id# 07903101

Eighteen Thirty Statesville

PO Box 36799

Charlotte, NC 28236-6799

901 Woodard Avenue

Parcel Id# 07903104

Jerry and Joyce Dellinger

506 Maymount Drive

Cramerton, NC 28032

|

1701 North Graham Street

Parcel Id # 07903103

Godley Management Company

Fred D. Godley

6132 Brookshire Blvd., Ste. C

Charlotte, NC 28216-2410

|

|

3. Representative photographs of the property: This report

contains representative photographs of the property.

4. A map depicting the location of the property: This report

contains a map depicting the location of the property. The UTM

coordinates are: 17 515172E 3900190N |

|

|

|

5. Current Deed Book Reference to the property: The most recent

deeds to these properties are listed in the Mecklenburg County Deed

Books: #03982/233; #07845/163; 03811/916; 10191/479; 05332/801.

The tax-parcel ID #s are: 07903101; 07903102; 07903103; 07903104;

07903105. 6. A brief historical sketch of the property: This

report contains a brief historical sketch of the property prepared by

Ryan L. Sumner.

7. A brief architectural description of the property: This

report contains a brief physical description of the property prepared

by Ryan L. Sumner.

8. Documentation of how and in what ways the property meets the

criteria for designation set forth in N.C.G.S. 160A-400.5:

a. Special

significance in terms of its historical, prehistorical, architectural,

or cultural importance: The Commission judges that the property

known alternatively as the Ford Motor Company Assembly Plant, Army

Quartermaster Depot, and Charlotte Army Missile Plant does possess

special significance in terms of Charlotte-Mecklenburg. The

Commission bases its judgment on the following considerations: 1.)

The Ford Motor Company Assembly Plant was an important component of

Charlotte’s industrial and commercial infrastructure in the early

twentieth century. 2.) The original Ford building is the work of

Albert Kahn, an industrial architect of national importance. 3.) As

the Quartermaster Depot during World War II, the complex and the

Charlotteans employed at the site played an important role in the war

effort by processing and distributing supplies, and repatriating war

dead. 4.) As one of two plants in the United States manufacturing

missiles for the Nike Program and the only one making the Nike

Hercules, the Charlotte Army Missile Plant and its local civilian

employees played a major role in the national defense of this country

during the Cold War.

b. Integrity of design, setting,

workmanship, materials, feeling, and/or association: The

Commission contends that the physical description by Ryan L. Sumner,

which is included in this report, demonstrates that the essential form

of the site meets this criterion.

9. Ad Valorem Tax Appraisal: The

Commission is aware that designation would allow the owner to apply

for an automatic deferral of 50% of the Ad Valorem taxes on all or any

portion of the property that becomes a "historic landmark.” The

current appraised value of the combined 74.202 acres of land is

$3,176,270.

The current appraised value of the improvements is $9,969,500. The

total current appraised value is $13,145,770. The property is zoned

I-2.

Date of Preparation of this Report: July 1, 2002

Prepared by: Ryan L. Sumner

Assistant Curator

Levine Museum of the New South

200 E 7TH St.

Charlotte, NC 28202

Telephone: 704.333.1887 x226

|

Historical Background Statement

Ryan L. Sumner

May 30, 2002

Detroit in Dixie: Ford Motor Company of Charlotte

Ford began operations in the Queen City during the company’s early

years. In his book, The Ford Factory, historian Lorin Sorensen

indicates that the Ford Motor Company opened a factory service branch

at 222 North Tryon Street in 1914 to supply service parts to Ford

dealers throughout the Carolinas.[1]

However, during its first year of operation, the popularity of the T

Model prompted Ford to begin assembling bodies in Charlotte onto

chassis shipped in from Michigan. [2]

In its first three months, the modified distribution facility produced

1,717 cars and in 1915, the facility’s forty employees built about

6,850 cars. By December 1915, the plant had the capacity to produce

eighty-five cars per day.[3]

As demand grew for the “Tin Lizzy,” the Charlotte branch outgrew its

North Tryon Street location and moved to a pre-existing building at

210 East Sixth Street. At this larger four-story and basement

facility, bodies and chassis were “completely assembled.” [4]

Again, increased automobile sales soon outstripped the plant’s ability

to produce, prompting Henry Ford to build a new factory specifically

designed for the mass-production of automobiles.

To build Charlotte’s newest manufacturing facility, Henry Ford turned

to renowned industrial architect Albert Kahn and building contractor

the McDevitt-Fleming Company of Charlotte. J. A. Jones Construction

of Charlotte and the American Sign Company of Kalamazoo, building the

oil tanks and water tower, respectively.[5]

Construction began on the Hutchison Farm at Statesville and Derita

Roads

[6]

in January 1924.

A series of photographs in the collection of the Henry Ford Museum and

Greenfield Village Research Center document the construction of the

Charlotte facility. [7]

The first photo, dated January 18, 1924, shows a cleared field where

the factory was eventually built. By February 29th,

steam-powered cranes and workers with mule-drawn wagons were preparing

the foundation. In May, the steel-frame structure of the building and

its service roads were nearly finished. The plant was complete enough

to begin manufacturing cars by September 14, 1924, despite a lack of

final additions. ,[8]

Images from August and September 1924 show the construction of the

plant’s powerhouse. The completed assembly plant, water tower with

emblazoned script “Ford,” is seen in the final photo dated January 26th,

1925. Throughout the series, African Americans are shown as the main

labor force in the construction of the plant, though it is unknown to

what extent Jim Crow laws and Charlotte’s Southern “traditions”

allowed blacks to be employed in manufacturing at the facility.

The total costs for the erection of the Statesville Avenue Ford plant

were: land and improvements: $130,442.07; buildings fixtures and

structures: $1,485,968.84; tools, machinery, and equipment:

$353,947.94; total investment: $1,970,358.85.

,[9]The

completed facility was 300 feet wide by 800 feet deep and boasted

240,000 square feet—approximately six acres—of production floor space.[10]

500 Charlotteans were employed at the Ford Motor Company during it

first year of production,[11]

when they assembled as many as 300 vehicles a day.[12]

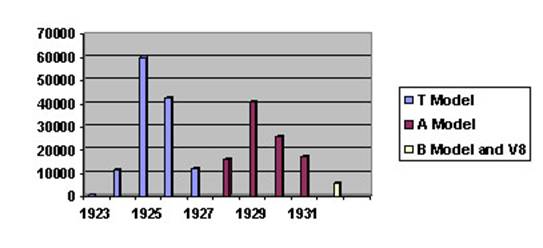

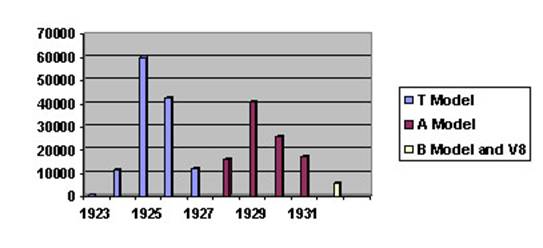

The plant produced up to 60,032 automobiles in a single year (1925),

manufacturing a total of 231,066 cars and trucks from 1924 to 1932.

|

Production

Numbers from Statesville Avenue Plant

Adapted from Information Supplied from Henry Ford Museum[13]

|

|

|

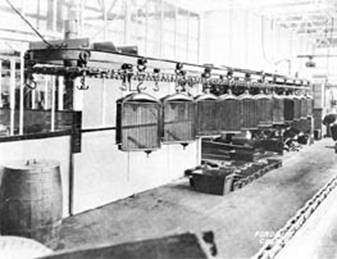

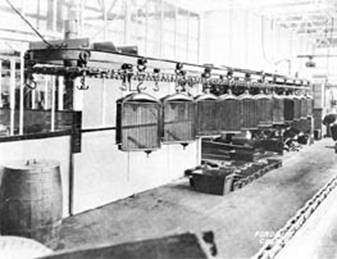

Grills Move Down the Assembly Line,

Statesville Avenue Ford Plant, 1925.

Collection of Levine Museum of the New South

|

Finished T Model Fords Roll Off the Line,

Statesville Avenue Ford Plant, 1925.

Collection of Levine Museum of the New South

|

|

The Stock Market Crash of October 1929 and subsequent Great Depression

took their toll on the automobile industry and spelled the beginning

of end for Ford production in Charlotte. As Southerners’ purchasing

power declined, so did production at the Statesville Avenue Plant,

plummeting from 40,947 units in 1929 to just 5,937 in 1932.[14]

Consequently, production ceased in 1932, with all service stock,

office and plant equipment relocated to other Ford facilities.[15]

The site was reopened in November 1934 as a sales and service branch.

The property was sold to the US Army in June 1941,[16]

with the company retaining space for branch operations temporarily,[17]

until operations were moved to 1000 West Morehead Street.[18]

|

|

Albert

Kahn: The Architect of Industry

Albert Kahn

(b.1860—d.1942),[19]

America’s foremost industrial architect, came from humble beginnings.

Kahn was born the son of poor Jewish immigrants to the United States,

which curtailed his formal schooling at the age of eleven. He dreamed

of being an artist, until a young Albert discovered he was colorblind.[20]

Kahn entered the world of architecture in 1884,

when the fifteen-year-old was given a non-paying job with

architectural firm of Mason and Rice. Here George Mason taught the

boy to draft and sketch. Kahn later won a scholarship to study

architecture in Europe, touring Italy, France, Belgium, and Germany.[21]

|

Architect Albert Kahn,

Courtesy of Albert Kahn Assoc. |

|

In 1895, Kahn founded his own firm, Albert Kahn

Associates. His early work included designs of Detroit’s first large

auto plants for the Packard Motor Car Company. The architect garnered

attracted great attention and admiration for his 1903 design of the

first concrete-reinforced automobile factory for Packard.[22]

[23]

His building was a remarkable improvement over the dangerous,

inefficient, timber-framed plants used by other automakers. Kahn’s

design was remarkably strong, fireproof, inexpensive to construct, and

was opened up by eliminating heavy obstructive columns.[24] |

|

Kahn’s work for Packard attracted the attention

of Henry Ford. For the next thirty years, these two self-made men

collaborated very closely and redefined the industrial process,

despite Ford’s widely-reported anti-Semitism.[25]

The first of 1,000 collaborations between the two was the Ford Motor

Company’s Highland Park Plant, which was defined by good lighting and

ventilation. However, Kahn’s greatest achievement was the 1917 design

of the Ford Rouge Plant—a half-mile-long, glass walled plant, where

production lines flowed continuously on one level, and 120,000

employees worked from raw materials to finished car.[26]

Albert Kahn, built about two thousand factories

for the automotive, aeronautical, and other industries between 1900

and 1940[27]—20

percent of all architect-designed factories in the U.S.[28]

Today, Albert Kahn is widely recognized as a revolutionary

industrial-use architect, but he never achieved recognition from his

peers, who had little respect for utilitarian buildings that did not

fit within the canon of public, civic, and residential architecture.

His Detroit firm still operates under the name

Albert Kahn Associates.

|

Queen City at War:

Quartermaster Corps Depot

Although the Japanese attack at

Pearl Harbor was a surprise, the US military had long foreseen

entanglement in the Second World War and had begun to prepare for

conflict. In Charlotte, these preparations included the establishment

of Charlotte Army Airbase (later called Morris Field) and huge

Quartermaster Depot.

The Charlotte Quartermaster Corps (QMC)

Depot was activated on May 16, 1941, initially with a staff of three

army officers and thirty-two civilians under the command of Lieutenant

Colonel Clare W. Woodward. Even before the site was officially

purchased, the QMC was setting up shop and soliciting construction

bids as Ford was moving their materials out.[29]

|

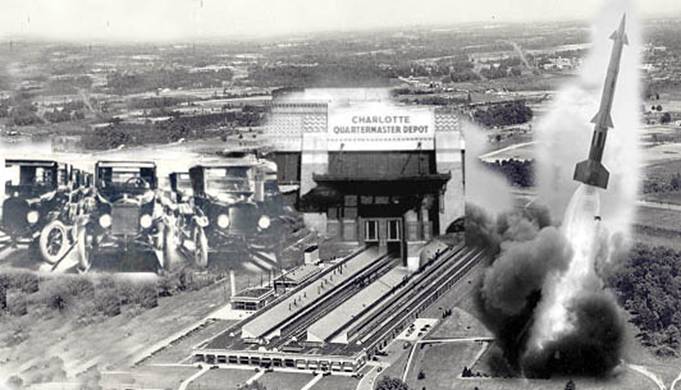

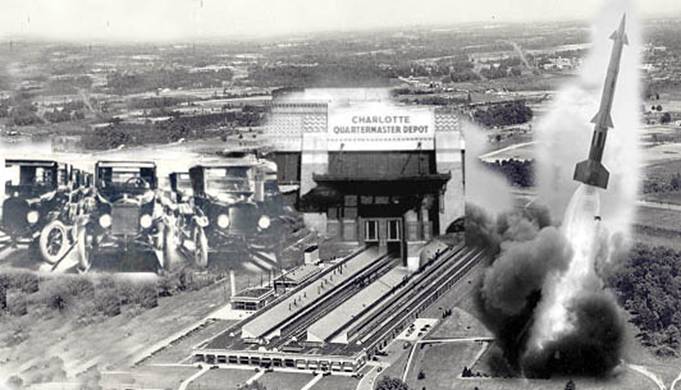

Aerial Photograph Showing the

former Ford Plant

and Additional Warehouses Built by the Army,

Circa Mid-1940s—1950s.

Collection of Levine Museum of the New South

|

The QMC wasted no time expanding the

facility and adapting it for their uses. On June 3, 1941, the War

Department awarded a general contract for construction of the first

three [of an eventual five additional] fireproof warehouses to the

William Muirhead construction firm of Durham. William Olsen and

William Deitrich, both of Raleigh acted as the structural engineer and

the architect for this initial expansion. The sense of urgency to

prepare for a coming war is evidenced by the fact that the Muirhead

Company was allowed “one day—today—to get ready to start this work,

because we must have it completed with the least possible delay.”[30]

The Charlotte News reported these first three additional

warehouses to be 180 by 12,000 feet.[31]

Two smaller warehouses, 180 by 600 feet, were added later and creating

a combined floor area of 1,000,000 square feet.[32]

Mechanized equipment played a large

role in the work done at the QMC Depot. Extensive rail lines

connected the six buildings together and to the Southern Railroad—the

facility saw a daily turnover of forty boxcar loads. It even had its

own diesel-electric GMC locomotive to move cars around the facility.

Gasoline-driven tractors and hoisting equipment were used to move and

stack heavy

|

cargoes, such as crates of canned

goods weighing of 1,000 pounds. In addition, small tractors were used

to pull long trains of “flatcars” about the warehouses. While the

operation was mostly train based, the QMC maintained a motorpool of

about 50 to 100 trucks for highway shipping.[33]

The QMC Depot grew well beyond its

original mission to supply US Army posts in the two Carolinas and

Virginia. The needs of the war saw the depot’s 2,500 civilian

employees and 80 Army officers processing “everything from toothpicks

to battle gear”[34]

for thirty-seven posts, camps, and stations in North and South

Carolina, Virginia, and West Virginia.[35]

While the primary purpose of the depot was as a distribution unit, it

was called upon numerous times during Word War II to send emergency

supplies overseas. In January 1944, the QMC Depot sent 745 tons of

materials through ports of embarkation, but by November of the same

year, export tonnage rose to 5,941 tons.[36]

The Charlotte operation became the Zone Inspection Headquarters,

supervising QMC units throughout the Southeast. Further, the depot

administered the Greenville, SC, Price Adjustment Office and handled

negations and contracts.

|

Above:View of QMC Deopt Railroad

Yards, 1942

Charlotte News, 1942.

|

Diesel-Electric GMC Locomotive used

to Move Freight Cars.

Charlotte News, 1942

|

From the end of the war to January

1949, the QMC Depot was used to repatriate the war dead. The American

Graves Registration Division (AGR) took over the depot in August 1946,

and returned the bodies of 5,170 deceased service personnel to next of

kins in North and South Carolina, Virginia, Tennessee, and Georgia.

At the peak of AGR’s work, the depot employed an escort attachment of

144 Army Ground Forces, 22 Air Force personnel, 10 Naval seamen, and

30 Marines. A plaque that honored these casualties of war was

dedicated at the depot’s main building by the Quartermaster General,

Major General Herman Feldman.[37]

However, this was not the end of the old Ford Plant’s patriotic duty.

|

Interior View of QMC Depot,

Charlotte News, 1942

|

Gods and Monsters: Cold

War-era Guided Missile Production in Charlotte

The Nike Project, named for the

Greek goddess of victory, was the United States’ and many of her

allies’ primary air defense system during the tense years of the Cold

War.[38]

In the final days of the Second World War, threats posed by advances

in offensive aircraft technology became obvious to the Army Ordnance

Department, which set about developing a guided missile system[39]

capable of destroying high-speed, high-altitude, maneuverable bombers

far beyond the range of conventional anti-aircraft artillery.[40]

After being green lighted in 1953, the Nike Ajax Weapon System was

deployed in March 1954, becoming the first land-based air defense

guided missile system to be deployed in America. The Douglas Aircraft

Company (DAC) was the principal production source for the Ajax Missile[41].

Ajax was capable of maximum speeds of over 1,600-mph and could reach

targets at altitudes of up to 70,000 feet within a range of about 25

miles. Initial production began at DAC’s plant in Santa Monica,

California, but the War Department announced in December 1954 that the

former Quartermaster Depot on Statesville Road would be used for the

manufacture of the Army’s Nike guided missile.[42]

|

Nike Ajax Missile on Launcher,

Boeing Corporate Archives

|

Adaptation of the former QMC Depot

into a guided-missile factory fell Charlotte Engineers Incorporated[43]

who did the design work for the project and to the Wilmington District

Army Corps of Engineers. Several different contractors did

construction work for different phases of the conversion, the largest

being Thompson Street Construction Company of Charlotte.

[44] The military

slated production to begin in July 1955, but unanticipated problems

rehabilitating the structures delayed the start until 1956.[45]

The site, designated the Charlotte Ordnance Missile Plant (COMP) and

later the Charlotte Army Missile Plant (CAMP), was operated by Douglas

Aircraft, who transferred thirty-five key executives and technicians

from Santa Monica. The plant hired about 1,500 personnel from

Charlotte, adding diversified employment to an area known primarily as

a textile center.[46]

|

Under the leadership of General

Manager Sheldon P. Smith, the plant preformed admirably. COMP

delivered its first Nike Ajax missile ahead of schedule in July 1956,

the beginning of a sustained flow of missiles form the factory doors

to deployment installations. The division won regard by never failing

to meet deadlines—delivering most of their quotas ahead of time. The

transfer of Nike Ajax design control to Charlotte in 1956 shows the

increasing importance of the Charlotte division.[47]

Between the two plants, DAC built 13,714 Nike Ajax missiles for

deployment at the 350 missile batteries in the US and overseas.[48]

|

In 1957, Douglas Aircraft began to

“tool up” and install new facilities for the production of the next

generation of Nike missile—the Hercules. The upgrades cost the

Department of Defense $21.5 million ($ 9 million for plant rehab and

$7.5 million in machinery).[49]

The Nike Hercules, or Nike B, was a

far more capable defensive weapon that the earlier Ajax and better

equipped to defend against smaller and faster targets, such as

supersonic planes and tactical ballistic missiles. This two-stage

missile contained a simplified solid fuel sustainer motor and was

designed to carry a nuclear warhead. Hercules had an increased range

of ninety miles, maximum range of 3,200 miles per hour, and the

capability to hit targets flying at altitudes over 100,000 feet.

Click here for a schematic drawing of the Hercules Missile.

The Charlotte Ordnance Missile Plant was the sole production site for

the Nike Hercules Missile. The major components for the missile

consisted of the missile airframe (forward and aft body, the main and

center fins, booster fins, and booster cluster), the warhead body

assembly, and shipping containers. As in the Ajax program, Western

Electric Company manufactured the guidance systems and ground

equipment in their three North Carolina plants.[50]

|

|

Although production of the Hercules

Missile dominated the activities at CAMP through 1965, Nike was not

the only project DAC and its workforce of 1,750 Charlotteans[51]

were working on. Production began in 1962 on the

Honest John XM50 Rocket, as did research and development for the

Nike Zeus. The early sixties saw work done for other military

agencies and NASA on aerospace vehicles, missilery, and military

hardware—such as infantry-carried anti-tank weaponry.[52]

On August 13, 1965, the Assistant Secretary of the Army determined

that retention of the plant could not be warranted under new polices

set by the Defense Department earlier that year. Despite formal

protest by the Hercules Project Manger, Secretary of Defense Robert S.

McNamara announced the close and subsequent disposition of the

installation. Missile production ended in May 1965, with repair parts

production continuing on a phase out basis until the last equipment

left the site in May 1967. After the close of the Charlotte plant,

Hercules manufacture was subcontracted by McDonnell Douglas (formerly

DAC) to the Mitsubishi Heavy Industries Company in Japan.[53]

Pat Hall Enterprises purchased the

property after McDonnell Douglas’s military contracts expired.[54]

Pat Hall then subdivided the property, selling parcels to the current

owners for manufacturing and warehouse space.[55]

|

Brief Architectural Description

Ryan L. Sumner

May 30, 2001

Site

Description

|

The property known as the Ford Motor Company Assembly Plant and later

as the US Army Quartermaster Depot and Charlotte Army Missile Plant

(hereafter referred to as “the plant,” “the site,” and “the complex”)

is situated in central Mecklenburg County, just north of the uptown

area. For the most part, the site fronts Statesville Avenue, which

bounds property to the west, Woodward Avenue is to the north, North

Graham Street on the east, and Armour Avenue to the south. The plant

is located along the former Southern Railway Line; several spur tracks

cross the site, linking the buildings to the main line. This

proximity to the railway let Henry and Edsel Ford ship their newly

assembled cars all over the Southeast and was obviously the

determining factor in positioning the plant on this location. The

complex is currently used as an office park by several companies and

in its current condition consists primarily of six mammoth buildings,

the boiler house, water tower, and associated smaller outbuildings.

The complex contains buildings erected and changed over a 35-year span

of time. The oldest parts of the site are the original Ford Motor

Company buildings designed by Albert Kahn and erected in 1924. Kahn’s

factory consisted of the main manufacturing building ( Building No.1),[56]

the boiler house (Building No.7), and a warehouse building (Building

No.8, no longer extant). In preparation for the United State’s

involvement in the Second World War, the Army Quartermaster Corps

added five additional warehouse-type structures (Buildings No.2—No. 6)[57]

to the site, using William Muirhead Construction as contractors, and

William Olsen and William Deitrich as structural engineer and

architect for the initial expansion. Buildings Nos. 3—4 are located

north of the Ford structures, while Buildings Nos. 4—6 are located

south of the original factory. The buildings were reshaped again for

guided missile manufacturing in the 1950s by Charlotte Engineers

Incorporated and The Wilmington District Army Corps of Engineer

contracting mainly through Thompson Street Construction of Charlotte.[58]

With the cessation of the missile program, Douglas’ equipment was

removed and the site was returned to warehouse functionality.

|

Building

Descriptions

The Front

Façade of Building No.1, c.1920s

Henry Ford

Museum & Greenfield Village[59]

|

Main Building (Building No.1):

Building No.1 was erected on the site as the principal manufacturing

space of Ford’s Charlotte assembly operation. The one-story structure

has a rectangular footprint and is approximately 300 feet wide (14

bays) by 850 feet deep.[60]

The building is brick-faced in

running bond, steel-framed, with concrete floors and a concrete

slab roof.[61]

Kahn was famous for opening up his manufacturing spaces to light and

the Charlotte facility follows the conventions established at the

Highland Park and Rouge Plants. The building’s steel frame supports

the weight of the roof, taking load-bearing responsibility off the

walls to allow the north and west sides of the building to be defined

by a band of multi-paned windows with metal muntins that run nearly

the length and about half of the overall height of the structure.

These windows are still mostly open on the north side of the building,

but have been painted over on the south. Light is further directed

into the space by two pairs of large wedge-shaped skylights that run

west-to-east along the length of the roof. Both the skylights and

wired glass windows opened for ventilation.

|

|

Detail of the

cornice from the northwest corner.

|

The west forward-facing façade is slightly

asymmetrical[62]

and consists of a central block flanked by projecting pavilions. The

facade runs the overall width of the building and wraps around the

northwest and southwest corners to a depth of about 2 bays. As seen

in the above photograph, 13 large windows once punctuated the west

face of the building; The 5 on the southern end were for show-room

display. Today these windows have been bricked-up, though their cast

stone sills are still in place. The central entrance with its

multi-pane wired-glass surround is still in place, but has been

boarded over and obscured by the placement of several trees. |

|

The front façade is defined by classical elements

given an art deco twist. 15 brick pilasters with cast stone[63]

caps visually support a cast stone architrave and frieze with

decorative brick tile laid in a herringbone pattern above the

pilasters and laid in a diamond motif across the spans. Above the

frieze is a heavily corbelled cornice featuring a row of small

diamonds.[64]

A large steel flagpole with a heavy concrete base

is located in front of Building No. 1. Early photos of the Ford plant

show the United States flag flown from atop the building’s central

block. Therefore, it is assumed that this large pole was added during

the days of the plant’s patriotic service. |

|

Broiler House (Building No.7) and Water Tower:

Building No. 7 was erected according to Kahn’s

design as part of Ford’s Charlotte Assembly Plant. The boiler house

sits atop an earthen plinth and has a footprint approximately 75 feet

square (14 bays wide). The exposed steel-frame building is faced in

horizontal cast stone bands and brick laid in

running bond, with concrete floors and slab roof.[65]

As with Building No.1, Kahn evokes elements from

Ancient Greco-Roman design; at the corners of the building, vertical

shafts of brick rise column-like terminating in plain concrete

capitals to support frieze and cornice-inspired elements. The roof

line appears to be slightly gabled, but this could be part of the

decorative neo-classical motif.

Perhaps the most defining characteristic of this

building is the extensive use of glass on each side of the building.

On the front western-face of the building, three horizontal rows of

windows span 12 columns with riveted steel beams between each and

steel muntins between the lights. The top two rows are composed of

3-over-3 sash windows. The lower two thirds of the central row have

the ability to tilt out for ventilation. The bottom band of windows

are 3-over-4 sash. Light pours into the space from all four

sides like a green house. |

Western face of the Broiler House,

Showing window sash, smoke stack, and

100,000-gallon water tower. |

|

While the structure is about as tall as a

three-story building, inside it is completely open from floor to

ceiling to accommodate the plant’s massive boiler.

Attached to Building No. 7’s northern side is the

boiler house’s smoke stack. The riveted steel cylinder is about 2 ½

times the height of the building and suffers from heavy oxidation.

Early photos of the site show that the stack was painted white with a

black cap.

Behind the boiler house, the Ford plant’s

original 100,000-gallon water tower rises up majestically on four

steel legs. The round tank is currently painted black and has a wide

conical top. Some early photos show the tower painted white with a

large script “Ford” painted on it.

|

|

Building No. 2

Western Face of Building No. 2, seen from Statesville Road.

|

|

Building No.2 was erected as part of the US Army Quartermaster

Corps Depot. The one-story structure has a elongated rectangular

footprint and is approximately 180 feet wide by 1200 feet deep.[66]

The building is brick-faced in “common

bond with six course headers,” steel-framed, with concrete floors

and a “high and low type” concrete slab roof.[67]

Unlike Albert Kahn’s buildings which celebrate natural light and

open-window ventilation, this structure is essentially a long brick

box, with almost no visible fenestration in the walls except for a few

very small louvered openings that occasionally punch through the

buildings imposing brick exterior. It appears from outside

observation that the only way natural light enters the space is

through a series of 10 clerestory skylights placed at regular

intervals along the length of the building that transverse the

building’s width. These monitors appear to be constructed from

pressed corrugated sheet-metal painted red with a bank of

15-pane-windows with steel muntins on the short sides (north and

south) and a series of 4 / 2-sash windows along the long east and west

sides.

Attached to the southwest corner of the building is a

guardhouse-type structure that appears to function as a secured

entrance. Many former employees of Douglas Aircraft have spoken about

the high-level of secrecy that dominated the operations at the plant;

a guardhouse reflects this desire for security.[68]

This small wooden structure is two bays wide by 4 bays deep. A

partial hip roof with modern asphalt shingles hangs over the

guardhouse and the short flight of concrete steps that connect it to

the ground.

Long concrete loading platforms abut the north side of Building No.

2, which faced spur rail tracks until recently.[69]

It was from here that the Quartermaster’s Corps received, processed,

and distributed the supplies needed by the war effort. Photos

published in the 1940s show the north face punctuated by numerous

industrial service doors.[70]

A open steel-framed structure with a rectangular footprint and a

slight gable spans the corridor between buildings No.2 and No.1. This

structure does not appear in the early QMC Depot photos and was most

likely built for DAC as part the overhead crane system used to lift

the missiles in nuclear fall-out shielded containers onto flatbed

train cars.[71]

|

|

Building No.3

|

|

Building No.3 was erected for warehousing for the

US Army Quartermaster Corps Depot. The one-story structure has an

elongated rectangular footprint and is approximately 180 feet wide by

1200 feet deep.[72]

The one-story building is about 27 feet high, with an east-west

running monitor roof that raises its height about 7 additional feet.

The structure is most likely steel framed and in early photographs

appears to be brick faced—today aluminum or vinyl siding covers the

much of the building’s exterior.

The working side of this structure is the

southern face, which once overlooked the site’s rail yards and

contains concrete loading platforms sheltered by broad eaves that run

the full length of the building. Many of the original industrial

loading doors seem to be present as does the original facing material.

The overhead cranes abut this side of the building and connect it to

building No. 2.

The western face of Building No. 1 is plain, but

is characterized by 8 bays of overhead tractor-trailer loading doors,

which are shaded by a rectangular metal canopy. |

|

Building Nos. 4, 5, 6

|

|

The QMC Depot constructed Building Nos. 4, 5, and 6 as a matched set.

They are one-story box-like structures brick-faced in “common

bond with six course headers ,” with elongated rectangular

footprints, steel-framing, and concrete floors and roofs.[73]

Multiple tall clerestory skylights rise from the roofs of each,

crossing the widths of the buildings at several intervals.[74]

These monitors are constructed from pressed corrugated sheet metal;

buildings 4 and 5 have 15-pane-windows with steel muntins on the short

sides (east and west) and a series of 4 / 3-sash windows along the

long east and west. However, these windows on No.6 have been covered

over.

All three buildings are about 180 feet wide, but there is

tremendous variation in the buildings’ overall length. Building No. 4

is only about 700 feet long, giving it the smallest floor space on the

site. Building No. 5 sprawls back 1200 feet, creating an area as

large as gigantic Buildings 3 and 4. It appears that building No. 6

was expanded some time before 1955; this new addition contains the

same steel framing and concrete floors, but the new addition is sided

with aluminum or vinyl and has a 6-foot single monitor that runs the

rest of the length from a mere 425 feet in length to over 1100ft.[75]

|

[1] Sorensen, Lorin, Ford Motor Company

[2]

Wadelington, Charles, History of the Charlotte, North Carolina, Ford

Motor Company Assembly Plant: 1914-1955 (Raleigh, NC: North Carolina

Department of Cultural Resources, Historic Sites Section, 1999), pg 4.

Courtesy of UNC Charlotte Special Collections.

[3]

Thompson, Edgar T., Agricultural Mecklenburg and Industrial

Charlotte, Social and Economic: 1926 (Charlotte, NC: 1926), P145

[4]

Wadelington, Charles, History of the Charlotte, North Carolina, Ford

Motor Company Assembly Plant: 1914-1955 (Raleigh, NC: North Carolina

Department of Cultural Resources, Historic Sites Section, 1999).

Courtesy of UNC Charlotte Special Collections.

[5]

City of Charlotte, Application for Building Permit No. 6122

(5/26/25); Henry Ford Museum and Greenfield Village Research Center,

Accession #429, Box 1, “Charlotte Branch History;” Henry Ford Museum

and Greenfield Village Research Center, Accession #721, box 7,

“Charlotte Branch History Photos.”

[6]

Kratt, Mary Norton, Charlotte: Spirit of the New South

(Winston-Salem, NC: John F. Blair Publishing, 1992), p138

[7]

Henry Ford Museum and Greenfield Village Research Center, Accession

#721, box 7, “Charlotte Branch History Photos.”

[8]

Charlotte Sunday Observer (September 14, 1924), Ford’s

Charlotte Plant as Viewed From an Airplane, pg. 1A

[9]

Based on records supplied to the Museum of the New South by the Henry

Ford Museum and Greenfield Village Research Center.

[10]

Charlotte Sunday Observer (September 14, 1924), Ford’s

Charlotte Plant as Viewed From an Airplane, pg. 1A

[12]

Wadelington, Charles, History of the Charlotte, North Carolina, Ford

Motor Company Assembly Plant: 1914-1955 (Raleigh, NC: North Carolina

Department of Cultural Resources, Historic Sites Section, 1999).

Courtesy of UNC Charlotte Special Collections.

[13]

Production by Year at the Statesville Avenue Plant: 1924: 10463 Cars,

1111 Trucks. 1925: 51708 Cars, 8324 Trucks. 1926: 36945 Cars, 5466

Trucks. 1927: 10221 Cars, 1617 Trucks. 1928: 13905 Cars, 1751 Trucks.

1929: 35634 Cars, 5313 Trucks. 1930: 21339 Cars. 4470 Trucks. 1931:

13259 Cars, 3603 Trucks. 1932: 4945 Cars, 992 Trucks.

[15]

Henry Ford Museum and Greenfield Village Research Center, Accession

#429, Box 1, “Charlotte Branch History.”

[16]

Mecklenburg County Deed Books, Book 1051, pg 239

[17]

Henry Ford Museum and Greenfield Village Research Center, Accession

#429, Box 1, “Charlotte Branch History.”

[18]

Once World War II broke out, Ford ceased to operate in Charlotte

altogether until they reopened a Parts Depot at 1000 W. Morehead Street

in the mid-40’s. A new Parts Depot was built at the corner of Wilkenson

Blvd. and Dixon Road, with the sales office, in 1952. the Charlotte

District Sales Office was moved to 309 Sharon Amity in October 1968.

[19]

For an in-depth examination of Albert Kahn’s life and career, see:

Frederico Bucci’s Architect of Ford (Princeton: Princeton

Architectural Press), 1994.

[20]

Albert Kahn Associates, History, Available online:

www.albertkahn.com

[22]

Bergeron, Louis and Maria Teresa Maiullari-Pontois,

Architecture Week,

The Factory Architecture of Albert Kahn:

01 November 2000 (Pg C1.1)

[23]

Albert Kahn Associates, History, Available online:

www.albertkahn.com

[25]

Bergeron, Louis and Maria Teresa

Maiullari-Pontois, Architecture Week,

The Factory Architecture of Albert Kahn:

01 November 2000 (Pg C1.1)

[26]

Albert Kahn Associates, History, Available online:

www.albertkahn.com

[27]

Bergeron, Louis and Maria Teresa Maiullari-Pontois,

Architecture Week,

The Factory Architecture of Albert Kahn:

01 November 2000 (Pg C1.1)

[28]

Bergeron, Louis and Maria Teresa Maiullari-Pontois,

Architecture Week,

The Factory Architecture of Albert Kahn:

01 November 2000 (Pg C1.1)

[29]

Charlotte Observer, (2/28/50), Charlotte’s QM Plant Hub of War

Activity; Charlotte Observer, (5/14/41), QMC Depot |

Officer, Staff Set to Arrive in Day or Two.

[30]

Greensboro News and Record, (6/4/41), Army Depots Award Made

at Charlotte.

[31]

Charlotte News (10/10/42), Warehouses Cover 72 Acres.

[33]

Interview of Capt. James Fancher, rtd, former military personnel at QMC

Depot (9/2/02).

[34]

Blythe, LeGette and Charles Brockman, Hornet’s Nest: the Story of

Charlotte and Mecklenburg County, (Charlotte: McNally of Charlotte

for the Public Library of Charlotte and Mecklenburg County, 1961)

p212-13.

[35]

Charlotte Observer, (2/28/50), Charlotte’s QM Plant Hub of War

Activity

[37]

Ibid; It is unknown if this plaque sill exists.

[38]

For a comprehensive analysis of the Nike and other US missile programs

see: John C. Lonquest and David F. Winkler, To Defend and Deter: The

United States Cold War Missile Program. Available on Microfilm at

Atkins Library, UNC Charlotte.

[39]

Western Electric Company, a division of Bell Labs developed the initial

feasibility, research, and design studies for this project under

contract to the Army Ordnance Department.

[40]

US Army Missile Command, Redstone Arsenal, Historical

Monograph—History of the Nike Hercules Weapon System (Project Number

AMC 75M, 19 April 1973), npg. Obtained from Freedom of Information Act

Officer Ms. Vickie Weatherman, US Army Aviation and Missile Command,

AMSAM-CIC, Redstone Arsenal, AL 35898, ph: 256.876.5763, fx:

256.876.2057

[41]Western

Electric Company produced the Nike Ajax guidance and ground systems in

their Winston-Salem, Greensboro, and Henderson, North Carolina plants.

Ibid; Charlotte Observer (12/30/54), Western Electric Gets

Guided-Missile Contract.

[42]

Partial Newspaper Clipping from the Mecklenburg ______, dated December

30, 1954. Clipping File: “Ford Plant,” Robinson-Spangler Carolina Room,

Public Library of Charlotte and Mecklenburg County

[43]

Located at the time at 3301/2 North Tryon Street.

[44]

Charlotte Observer (12/21/55)Contract Let in Nike Expansion,

1B; Charlotte News (12/12/55), Missile Plant Contract is Let;

Charlotte News (12/29/55), Installation of Nike Batteries

Stepped Up; Charlotte Observer (1/18/58), Missile Plant

Building Plans Now Complete.

[45]

Douglas Aircraft Company Yearbooks, (1955) Boeing Aircraft

Archives.

[47]

Douglas Aircraft Company Yearbooks, (1955, 1956, 1957) Boeing

Aircraft Archives.

[49]

Douglas Aircraft Company Yearbooks, (1957) Boeing Aircraft

Archives.

[50]

US Army Missile Command, Redstone Arsenal, Historical

Monograph—History of the Nike Hercules Weapon System (Project Number

AMC 75M, 19 April 1973), npg. Obtained from Freedom of Information Act

Officer Ms. Vickie Weatherman, US Army Aviation and Missile Command,

AMSAM-CIC, Redstone Arsenal, AL 35898, ph: 256.876.5763, fx:

256.876.2057

[51]

Employment figure from: Douglas Aircraft Company Yearbooks,

(1961) Boeing Aircraft Archives.

[52]

Douglas Aircraft Company Yearbooks, (1960, 1961, 1962, 1963,1964)

Boeing Aircraft Archives.

[53]

US Army Missile Command, Redstone Arsenal, Historical

Monograph—History of the Nike Hercules Weapon System (Project Number

AMC 75M, 19 April 1973), npg. Obtained from Freedom of Information Act

Officer Ms. Vickie Weatherman, US Army Aviation and Missile Command,

AMSAM-CIC, Redstone Arsenal, AL 35898, ph: 256.876.5763, fx:

256.876.2057

[54]

Mecklenburg County Deed Books (#2055, pg266), dated February 9,

1959.

[55]

Charlotte Observer (1/3/76) Eckerd Purchases old Douglas Site,

p8. See also list of most recent deeds at the top of document.

[56]

This system of numbering the buildings is the one used by the Sanborn

Fire Insurance Company and the US Army Corps of Engineers.

[58]

This information is presented in greater detail with citations in the

history section of this document.

[59]

Photographic Collection of Henry Ford Museum & Greenfield Village

833.Box4.Folder 7B P.833-70736

[60]

Maps of the Sanborn Fire Insurance Co., Charlotte,

(1929 edition—Corrected through 1955), p331. Mecklenburg Geographic

Information System

[62]

The southern pavilion is one bay wider than the northern one.

[63]

That theses elements are “cast stone” is reported in: Sarah A. Woodard

and Sherry Joins Wyatt, Industry, Transportation, and Education: The

New South Development of Charlotte and Mecklenburg County (David

Gall Architect, 2001). Available online:

www.cmhpf.org/hlc/surveyindustrialsurvey.htm

[64]

This frieze may have been created by the Detroit-based

Pewabic Pottery, a nationally renown producer of ornamental art deco

architectural tiles and one of Albert Kahn’s favorite vendors.

[65]

Maps of the Sanborn Fire Insurance Co., Charlotte,

(1929 edition—Corrected through 1955).

[68]

Interview of Laurin Quillen, former Douglas Aircraft employee (9/9/02).

Interview of RoyceMcNeil, former Douglas Aircraft employee (11/17/02).

The plant was divided into several color-coded zones that corresponded

to security clearance indicated by colored badges: yellow/hourly,

green/salary, black/confidential, red/secret, unknown color/top secret.

Before entering the plant, employees had to check in with the guards who

checked identifications and conducted sporadic searches and FBI

background checks.

[69]

A 1996 hazardous materials survey by the US Army Corps of Engineers

shows the tracks extant, but a they are not visible in a 2000 aerial

photo of the site by the Mecklenburg Geographic Information Service.

[70]

Charlotte News (10/10/42), Warehouses Cover 72 Acres.

[71]

Interview of James B. Lisk, former Douglas Aircraft employee (9/9/02).

Interview of RoyceMcNeil, former Douglas Aircraft employee

(11/17/02).

[73]

Maps of the Sanborn Fire Insurance Co., Charlotte,

(1929 edition—Corrected through 1955).

[74]

There are six monitors on building No.4, ten monitors on building No.5,

four on No.6.

[75]

Maps of the Sanborn Fire Insurance Co., Charlotte,

(1929 edition—Corrected through 1955).

|

|