https://www.baltimoresun.com/maryland/carroll/news/cc-nike-missile-cap-20191208-gnpb5ilh7jbl7kwytdra7fqbf4-story.html

Carroll County Times

Dec 08, 2019

GRANITE — At first glance, the expanse of faded blacktop at the back of a lot on Hernwood Road at the southeastern edge of Carroll County looks a lot like a parking lot, if you excuse the odd metal and concrete protrusions. And it actually has served as a parking lot at one point in its life.

But that was before the Civil Air Patrol moved in and discovered the piece of history in their new back yard.

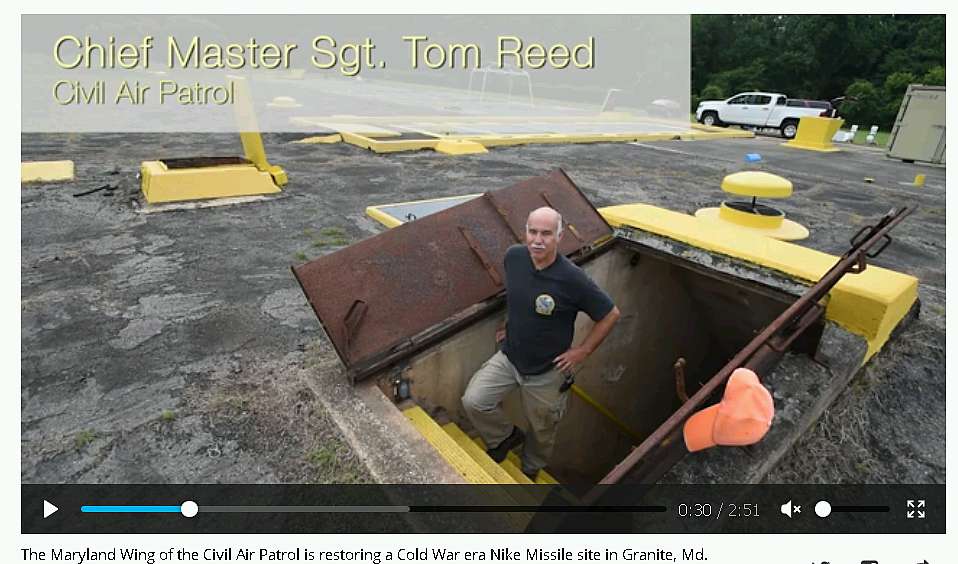

“What’s interesting about this site is it’s also an abandoned Nike missile site,” Civil Air Patrol CMSgt. Tom Reed said. “Nike missiles were anti-aircraft missiles. They were used during the Cold War to protect, for this area, Baltimore and Washington, [D.C.] from Soviet bombers.”

On a hot day in August, Reed stood on the blacktop surrounded by cans of Rust-Oleum, black and yellow paint, and scrapers — the tools for his project of returning the site to some semblance of its former Cold War glory.

Volunteers, Luke Then, left, and Dan Schoen, clear weeds from the asphalt surface of the launch site while working to

restore the BA-79 Nike Missile site in Granite Saturday, June 15, 2019. (Dylan Slagle / Carroll County Times)

1 / 36

Volunteers Joseph Zalek, left, and Dave Beattie, both Petty Officers 2nd Class in the US Navy, clear thick mats of weeds from

the asphalt surface of the launch site while working to restore the BA-79 Nike Missile installation in Granite Saturday,

June 15, 2019. (Dylan Slagle / Carroll County Times)

“Maryland Civil Air Patrol is actually working to fix this up,” Reed said. “We’re trying to repaint all the metal, keep it from corroding. We are painting all the concrete back to what it looked like back in the ’60s.”

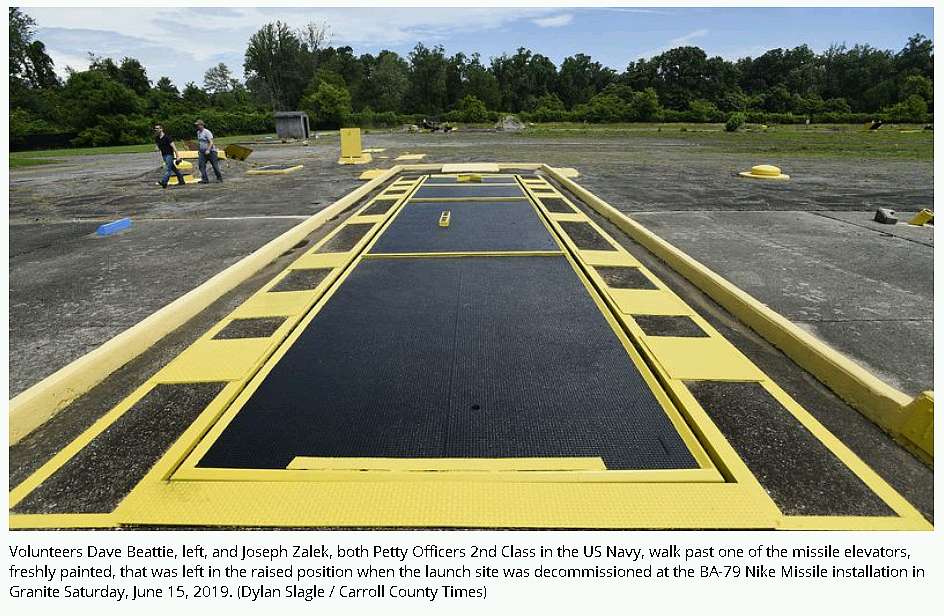

What the site looked like in the ‘60s, apart from the sharp-finned Nike missiles rising above their launch pads, was the black and yellow striping on the concrete lips around the openings to the stairwells and elevators that lead to the heart of the site, the command rooms and missile magazines, which still lie below the banal black surface.

With the help of volunteers, Reed has been working diligently on the restoration project for more than two years. Hard work, but worth it in his estimate — after all, these weren’t just any missiles.

“There were nuclear weapons here,” he said.

Project Nike

In the early 1950s, U.S. Army Cold War defenses of Baltimore and D.C. included ringing both cities with more than a dozen anti-aircraft gun batteries, of which the site in Granite was one. The site was given the designation BA-79 — BA for Baltimore and 79 because that was the angle, in degrees, from Baltimore’s center.

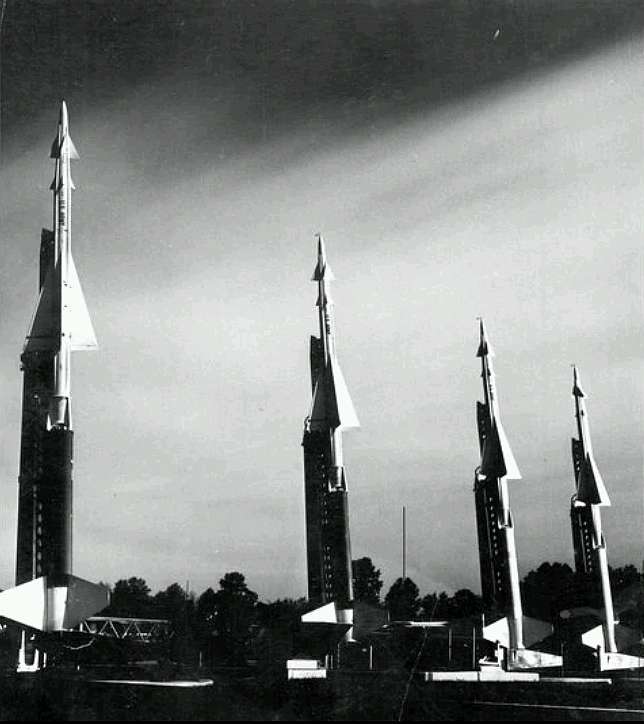

By the middle of the decade, rocket technology had advanced enough that these sites could be converted to missile batteries armed with the Nike Ajax, according to Civil Air Patrol Lt. Col. Bob Midkiff, who has been steeping himself i n the project’s history.

“The Nike Ajax was a two-stage rocket. One stage of it was solid fuel, and the other one was a liquid propellant,” he said. “The liquid propellant was like really nasty stuff. It was corrosive and toxic, and just handling it, you had a hazmat suit out and, you know, the whole works.”

By 1960, however, the site had been upgraded to the Nike Hercules. An all-solid-fuel rocket, the Hercules eliminated the need for hazmat protocols, and with a range of more than 75 miles, the Hercules had far greater reach than the 25-mile range of the more limited Ajax.

But the most significant difference was in armament: The Hercules carried a nuclear warhead ranging in yield from 2 to 40 kilotons — that is, generating a blast as powerful as up to 40,000 tons of TNT high explosive. The bomb dropped on Hiroshima was a 15-kiloton yield weapon.

All that firepower, however, was tied to 1950s analog technology, Midkiff notes, with a targeting radar installation about a mile down the road from BA-79 that couldn’t handle multiple projectiles.

“Of the eight sites that are surrounding Baltimore, each site could fire and track one missile at a time. So if you have an incoming bomber fleet, the first site fires a missile, the second site fires a missile, third site, and they rotated it around,” he said. “Hopefully, when they get back to it again, their missile has hit the target and they’re ready to launch their second.”

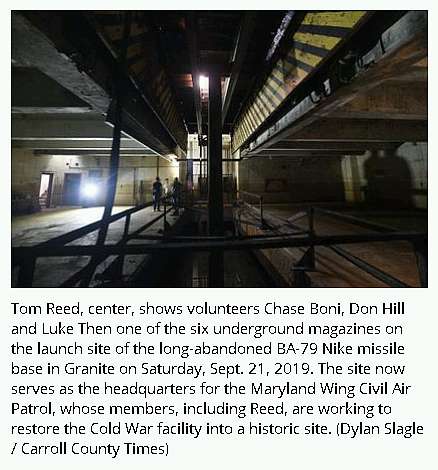

Granite hosted what is known as a double site, according to Reed, equipped with both the Ajax and Hercules Nike missiles stored in six subterranean magazines, and up to 24 above ground on a rail system, their warheads pointed toward the sky.

Pfc. Crawley

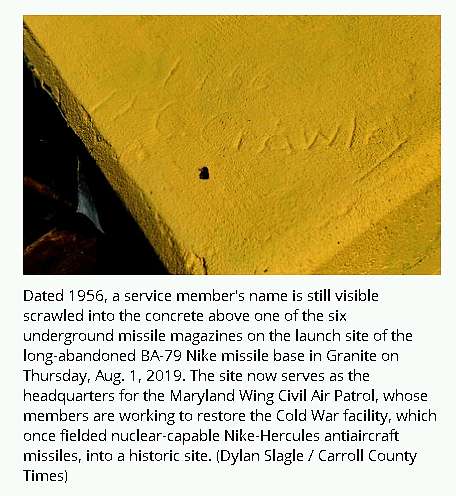

Under the hot August sun, Reed noticed something in the concrete he had missed while painting it bright yellow.

“Looks like somebody wrote ‘1956 PFC Crawley,' " he read from the concrete. “I just saw that.”

That memo from a different time was the kind of unexpected human touch that got Reed interested in restoring the site in the first place — to give people a chance to understand the mindset of a different era.

Take the very existence of the Nike Hercules missile on that particular site, and pointing north.

“These had a range of 75 miles. North 75 miles? You’re not even in Pennsylvania,” Reed said. “Or maybe you’re in Pennsylvania, but they’re going to detonate a nuclear warhead above Pennsylvania. You know, they thought that was an acceptable risk.”

It’s impossible to know if it was an acceptable risk for Pfc. Crawley. Like other regular Army troops assigned to the site, he would have lived onsite in the barracks (later in the 1960s, the site would be operated by National Guardsman who lived in the community). He would have helped fuel the Nike Ajax missiles when they arrived, or helped assemble the warheads and attach them in the small building dedicated to those armaments. But if he ever had to scramble for the real deal, he had to know that even in victory, there was a large chance that his community, and his brothers in arms, would have a hard time riding things out.

The Underground

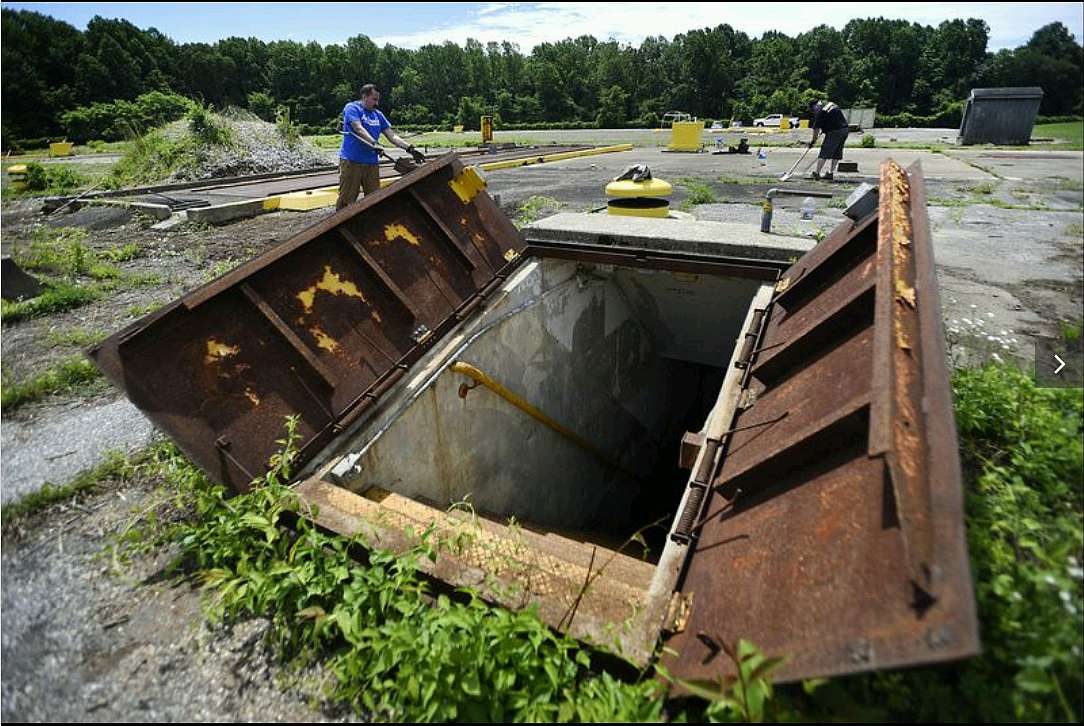

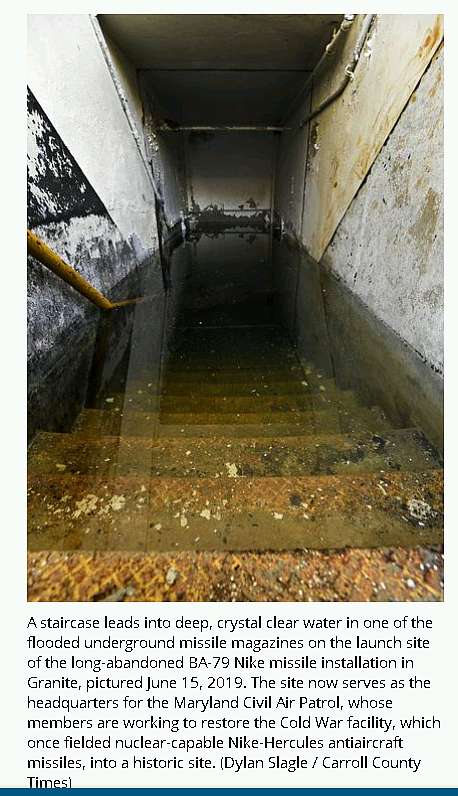

The magazines, tennis court-sized concrete caverns that once held additional Nike missiles in preparation for a potential doomsday, are accessed by double steel blast doors in a concrete shroud that don’t look much different than the doors to any residential cellar. The state had welded all the doors shut years ago, Reed said, but breaking those metal bonds was hardly the most difficult barrier to accessing the history beneath the site’s surface, as he demonstrated by opening the doors to one of the magazines he had yet to fully tackle as part of the project.

A staircase leads into deep, crystal clear water in one of the flooded underground missile magazines on the launch site of the long-abandoned BA-79 Nike missile installation in Granite, pictured June 15, 2019. The site now serves as the headquarters for the Maryland Civil Air Patrol, whose members are working to restore the Cold War facility, which once fielded nuclear-capable Nike-Hercules antiaircraft missiles, into a historic site.

“This is 30, 40 years of rainwater,” he said, a statement it takes a moment to appreciate as the view down the 24 steps to the bottom to the straight stairwell was perfectly unimpeded. After decades in the underground cistern, any debris had settled out, and it takes a close look to realize the crystalline water line reaches up past the middle of the stairs.

“Each step takes about two to three hours to pump down one step,” he said. “So these 11 steps, so you're talking about six days of pumping.”

By mid-August, Reed had managed to completely pump out two magazines, and despite the rivulets of rust on the walls and lack of lighting, the faded paint scheme is still visible.

“This is kind of what we want to go back to down below: the green, the black, white to the trim,” Reed said, his voice echoing in the concrete chamber. “That's what the color of the buildings were, light green with a dark green trim.”

Though there is a tension between the impulse to restore and the impulse to preserve. In one magazine, Reed pointed out a Shaefer beer can lodged atop a corroding piece of conduit.

“Somebody tried to move that, and I said, ‘Put it back. That’s history,’ ” Reed said.

In the center of the magazine ceiling, pricks of light could be seen, cracks in the metal doors of the elevator that would have raised the Nike missiles to the surface had the first 24 missiles topside already been fired off, and the apertures through which the rainwater had infiltrated the abandoned space.

But the magazines are not where someone like Pfc. Crawley would have been had the site been activated in an actual attack. A small but solid metal blast door separated each magazine chamber from a narrow corridor that led to the small control room. It’s there the soldiers would have rallied to during an alert to await orders to fire.

It would likely have been harrowing, according to Midkiff.

“The magazines are not bomb proof. They’re not designed to ride out, you know, nuclear winter or anything,” he said. “What they were designed for is if a missile catches fire and blows up inside, it won’t hopefully blow up the others around. There’s actual ground like hard ground between each one of the magazines.”

But for Reed, the real psychological tension would have come from thoughts about what was taking place up above ground, especially by the later ‘60s, when the site was staffed primarily by local Army National Guardsman.

“Their houses were around here. That means there’s bombers coming in to actually take out D.C. and Baltimore,” he said. “That’s my family.”

Nike’s end

By the end of the 1960s, the threat began to change as the Soviet Union, like the United States, began mass producing intercontinental ballistic missiles, or ICBMs, which could be fired from silos or from submarines and could rain nuclear warheads on American cities from space in little more than a half hour. The Nike Ajax and Hercules were designed to take down Russian strategic bombers, such as the Tupolev Tu-95 “Bear” — not nuclear warheads screaming back into the atmosphere at 15 times the speed of sound.

But it was treaty obligations as much as technical deficiency that spelled the end of the Nike sites, according to Midkiff. “As part of the [Strategic Arms Limitations] One Treaty, both sides basically agreed to limit their inventory,” he said. “The Nike missile by then, you know, it's an analog system, it was pretty much an obsolete system. So within the continental United States, they went ahead and started phasing them out.”

The nearly 300 Nike missile sites across the United States, from Granite to Chicago to San Francisco, were phased out by the early ‘70s. “This one was done by ’74 for sure,” Midkiff said. “So the property was handed over to the state.”

For anyone interested in the history, Reed said, that may have been a fortuitous handoff. “It’s pretty well intact,” he said. “Most sites have been either covered over, bulldozed or used for other purposes, so this site has some historical significance.”

A healthy obsession

Reed’s own appreciation of the site’s history began in 2015. That’s when the Maryland Civil Air Patrol, forced from its former headquarters near Baltimore-Washington International Thurgood Marshall Airport — the old buildings were condemned — was offered a lease on the Granite site by the state.

“I saw this, said, ‘This is cool. What is it?’ And I just started cleaning it up,’ ” he said.

“Then it became an obsession,” added Civil Air Patrol Lt. Col. Brenda Reed, Tom Reed’s wife and the Maryland Civil Air Patrol’s chief of staff, as well as a former commander of the Carroll County Composite Squadron. “He has a workday like once a month, and more and more people are getting interested.”

A lot of that early work was weed-whacking and pulling up the woody shrubs that had overgrown much of the lot over the decades, along with the hard work of using shovels to scrape the rust from the long, rectangular metal missile elevator doors.

The painting work is less laborious, but still painstaking, Tom Reed and Midkiff noted, and they are not even aiming for a fully operational restoration of the site. “Some of it’s going to be just too cost prohibitive for us,” Midkiff said. “They have a fully restored base out in San Francisco and just to do a door like the doors that you see here, to get them authentically, completely redone, cost the park service like $17,000.”

The San Francisco site — SF-88L — even has working hydraulics and decommissioned Nike missiles in the magazines, something BA-79 will never see again, but Reed said they might well get a close facsimile. “One of our squadrons actually wants to build a mockup of the missile, of both missiles, full size,” he said. “Some guys are engineers from Northrop Grumman up there in Cumberland, and they want to actually build it to the exact specs.”

But it isn’t just a matter of personal interest, Brenda Reed notes. The Civil Air Patrol, as a nonprofit, civilian auxiliary of the U.S. Air Force, has three primary missions: It’s civilian cadet program for youth, air search and rescue during emergencies, and aerospace education.

“This falls right in line with that third mission,” she said. “This is air education. It’s aerospace history, and it will involve the community.”

But back in its heyday, the BA-79 site was not always a source of good community relations. That could have started with the Army getting the property from a local farmer by eminent domain, according to Midkiff.

“They weren’t too happy about that,” he said. “They went to court and they fought it out in court and they got a higher price for the land, but ultimately the Army got the land and a lot of bad feelings with neighbors.”

It might not have helped either, that, according to interviews Tom Reed conducted with a former Army officer stationed at the site, that the toxic Ajax fuel might have been responsible for killing local livestock. “He said, ‘we paid for a couple of cows.’ ”

Then, of course, there was no way to know if a drill conducted on the base was, in fact, just a drill.

“Imagine that, you know, waking up at three o’clock in the morning, you hear sirens blaring here and a mile down the road. Next thing you know, you see missiles rising up out of the ground because they’re running a drill at three o’clock in the morning,” Midkiff said. “You don’t know if it’s the end of the world coming or not.”

Neighborhood relations

“My husband, when we started dating, we went to a church all the way over in Catonsville because of that,” Beverly Griffith said. Griffith has lived within a half-mile of the Nike site in Granite her entire life, in one house or another, and in 1958, she met her late husband there — Private Robert Franklin Griffith came to serve at the site from his home in Alabama, back when the site was still a regular U.S. Army installation.

“We had, at the time, two or three different churches, and they seemed to welcome at some and others they weren’t. I don’t know why,” she said. “There was some kind of a mystery about it. I don’t think there were any community-type meetings on it or like that. It allowed rumors to abound.”

Rumors such as one that there was a tunnel running from the missile site to the location where radar antennas sat a mile down Hernwood Road.

“I heard the crazy things, you could drive a jeep through it, but I don’t believe it’s true in my opinion,” Griffith said. “It could have been something for electrical wires or piping.”

The Civil Air Patrol folks, meanwhile, haven’t found any evidence of tunnels large or small, according to Tom.

“And nobody’s ever admitted that that actually worked here,” he said.

But not all of the neighbors were displeased with the Nike site, or thought it was that mysterious. Lt. Jay Landsman of the Baltimore County Police Department has also lived in the area since the missile site’s heyday, as have his relatives — his brother-in-law worked on the site — and remembers what the site looked like during the tense parts of the Cold War.

“I remember coming home during the missile crisis and they had the missiles sticking out of the ground, the Cuban Missile crisis,” he said. “It was pretty cool.”

But regardless of how the former Nike site and the community might have interacted in the past, both Landsman and Griffith thought the Civil Air Patrol’s renovation plan was a good idea.

“I think it’s great. We’ve had a lot of issue with the county and the state about what was going to be done with [the Nike site], and we could never get any clear answers. But I think that’s a good answer.”

‘A picnic around the nukes’

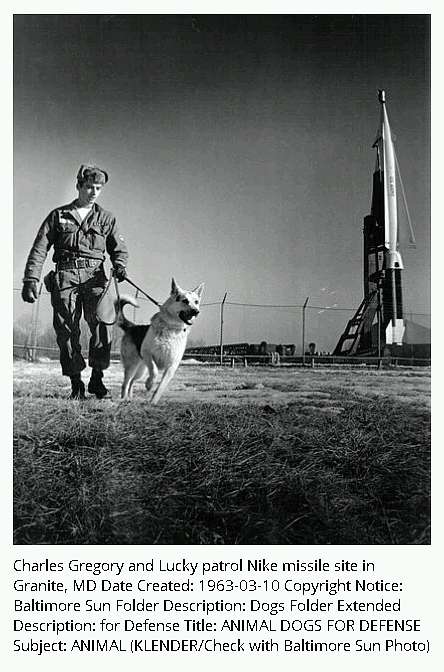

Whether the Nike site was mysterious to the neighbors at the time of its operation or not, it certainly wasn’t an inviting spot, fenced off and guarded by fierce dogs, Tom Reed noted.

“They knew about it, but they were not allowed on here,” he said. “They didn’t have family days, ‘Come on down here and have a picnic around the nukes.’ ”

That’s why Reed’s plan is to eventually open the site up to the whole community, not just members of the Civil Air Patrol. His initial, only half-joking marketing plan is to put up some flyers at the Woodstock Inn, a local biker bar. “I was here working Saturday night, looked up, and there’s these three bikers that had just come in. We have a 9/11 Memorial here, and they were just looking at that,” Reed said. “I mean, come on, bikers are patriotic Americans, and we say, ‘Hey, there’s a Cold War-era missile site, come by.’ ” In the meantime, however, there’s still a lot of work to be done, and the Civil Air Patrol could use volunteers for workdays, as well as monetary donations. “One gallon of Rust-Oleum costs $40,” Reed said, “and that stupid elevator is like six gallons.”

Those interested can learn more at the Facebook page that’s been set up for the project at

www.facebook.com/groups/219699235388622/.

There will be plenty of remaining work to go around. It’s been two years already, and there’s not a set date for the site to

open up to the public, but for Reed and his colleagues, it will be worth the wait.

“The long-term vision is you open this up once a month, advertise it so people can come down they can see the history,”

he said. “I mean, most people don’t know that we had these sites here.”

|

BALTIMORE SUN FILE PHOTO Nike Ajax antiaircraft missiles stand on their launchers at the BA-79 Nike missile site in

Granite in 1953. (KNIESCHE/BALTIMORE SUN)

Jon Kelvey

e-mail, jon.kelvey@carrollcountytimes.com

re: https://www.baltimoresun.com/maryland/carroll/news/cc-nike-missile-cap-20191208-gnpb5ilh7jbl7kwytdra7fqbf4-story.html

Jon Kelvey joined the Carroll County Times in 2014 after two years with sister publication, The Advocate of Carroll County. Prior to working with the Times, Jon spent 10 years in the California wine industry. He is a graduate of UC Berkeley with a degree in Cognitive Science. Reach him at 410-857-3357.