Cray-1A

ENIGMA

Apollo Guidance Computer

Apple-1

Altair BASIC Paper Tape

Xerox PARC Alto

MITS Altair 8800

BUSICOM Calculator

IBM THINK Sign

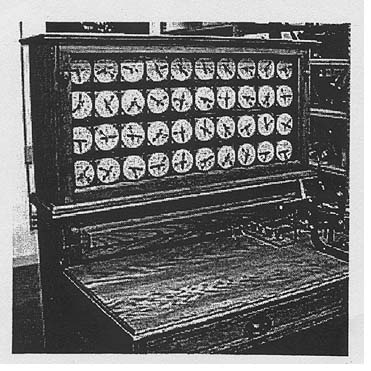

Hollerith Census Machine

-

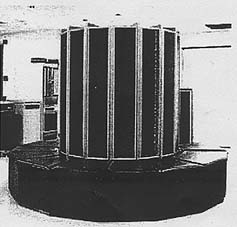

Cray-1A (1976)

Accession Number: X1553.98 A-G

Gift of Lawrence Livermore Laboratories. -

As Control Data Corporation grew aggressively into a major company

on the basis of its supercomputer sales, its bureaucracy became

onerous to Seymour Cray who, in 1972, left to start his own company.

His venture, called Cray Research Inc., was founded in his hometown of

Chippewa Falls, Wisconsin, and had a modest staff of about 40 persons.

As Control Data Corporation grew aggressively into a major company

on the basis of its supercomputer sales, its bureaucracy became

onerous to Seymour Cray who, in 1972, left to start his own company.

His venture, called Cray Research Inc., was founded in his hometown of

Chippewa Falls, Wisconsin, and had a modest staff of about 40 persons.

- Working in seclusion for four years, Cray introduced the Cray-1 supercomputer in 1976. Like all of Cray's machines, the Cray-1 was the fastest computer in the world at time of introduction. Speed was always Cray's prime design goal and, given large cold war defense budgets, funding was rarely an issue for typical CDC/Cray customers. The Cray-1's unique physical design earned it the title of "the world's most expensive loveseat," a reference to the concentric bench that surrounds the main tower.

- However, this bench is functional as well as aesthetic since underneath it lies part of the machine's power supply and air conditioning system. The overall circular shape reveals a similar blend of practicality and symbolism: the shape allows wire lengths to be kept as short as possible, and architecting of memory and processing elements to be integrated both physically and logically. Viewed from above, the 'C' shape also alludes to the Cray name. The machine was wired almost completely by hand and used a Freon cooling system. Monthly operating cost, including service contract, was approximately $100,000.

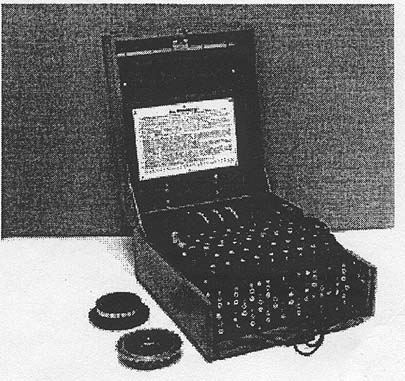

- ENIGMA (Wehrmacht) (1943)

Accession Number: XB197.81 Loan

from Gwen & Gordon Bell. ENIGMA-like machines were first created in the 1920s as a means of

encrypting business communications and were sold as a commercial product by

several German and Swiss firms. During WWII, it became apparent to certain

allied codebreakers that the German military was using a cryptographical

system based on these machines for securing battlefield communications.

With a dedicated team of people from highly diverse backgrounds, British

codebreakers at Bletchley Park near London built the Colossus machine and

were thus able to decrypt most three-rotor ENIGMA traffic by early 1941, a fact

of incalculable importance to the eventual Allied victory, particularly in

ending the devastating shipping losses during the U-boat war (1940-41). ENIGMA, also

known as "Ultra," was never discussed openly until 1974 when the British

government declassified key documents and permitted public disclosure of the project.

ENIGMA-like machines were first created in the 1920s as a means of

encrypting business communications and were sold as a commercial product by

several German and Swiss firms. During WWII, it became apparent to certain

allied codebreakers that the German military was using a cryptographical

system based on these machines for securing battlefield communications.

With a dedicated team of people from highly diverse backgrounds, British

codebreakers at Bletchley Park near London built the Colossus machine and

were thus able to decrypt most three-rotor ENIGMA traffic by early 1941, a fact

of incalculable importance to the eventual Allied victory, particularly in

ending the devastating shipping losses during the U-boat war (1940-41). ENIGMA, also

known as "Ultra," was never discussed openly until 1974 when the British

government declassified key documents and permitted public disclosure of the project.

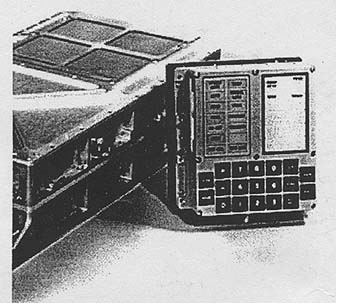

- Apollo Guidance Computer (1968)

Accession Number: X37.81 A-B Gift of

Charles Stark Draper Lab, MIT. In 1968, the Apollo Guidance Computer (AGC) made its debut orbiting the Earth

on Apollo 7. A year later, it steered Apollo 11 to the lunar surface.

Astronauts communicated with the computer by punching two-digit codes

and the appropriate syntactic category into the display and keyboard unit. Using

the computer's display keyboard, known as the "DSKY" (pronounced "Diskey"),

an astronaut could interact with the machine's navigational

functions by using a "verb" + "noun" syntax, for e.g. "Display" + "Velocity."

In 1968, the Apollo Guidance Computer (AGC) made its debut orbiting the Earth

on Apollo 7. A year later, it steered Apollo 11 to the lunar surface.

Astronauts communicated with the computer by punching two-digit codes

and the appropriate syntactic category into the display and keyboard unit. Using

the computer's display keyboard, known as the "DSKY" (pronounced "Diskey"),

an astronaut could interact with the machine's navigational

functions by using a "verb" + "noun" syntax, for e.g. "Display" + "Velocity."

- With few moving parts and no vacuum tubes, it was rugged and compact. Two DSKYs were installed on the Command Module: one on the main instrument panel and another near the passageway to the Lunar Module. The Apollo project, and in particular its computer, was a major impetus to the development and improved manufacturability of integrated circuitry (IC).

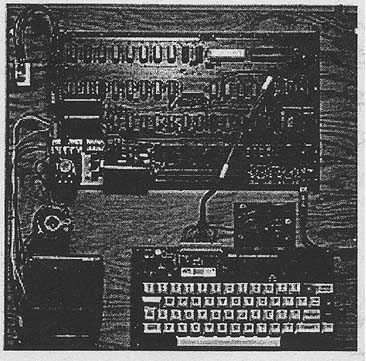

- Apple-1 (1975)

Accession Number: X210.83

Gift of Dysan Corporation. The Apple-1 was designed by California youngster Steve Wozniak as

a "way of showing off' to his friends at the Homebrew Computer Club. For

$666.66, the buyer received the Printed Circuit Board (PCB) shown

here, a bag of parts, and a 16-page assembly manual. When Mountain

View computer store, The Byte Shop, in ordered 50 of these, Wozniak and a

friend, Steve Jobs, went into smallscale production. Based on the success of

the Apple-1's sales, "the two Steves" attracted financing and started Apple Computer.

The Apple-1 was designed by California youngster Steve Wozniak as

a "way of showing off' to his friends at the Homebrew Computer Club. For

$666.66, the buyer received the Printed Circuit Board (PCB) shown

here, a bag of parts, and a 16-page assembly manual. When Mountain

View computer store, The Byte Shop, in ordered 50 of these, Wozniak and a

friend, Steve Jobs, went into smallscale production. Based on the success of

the Apple-1's sales, "the two Steves" attracted financing and started Apple Computer.

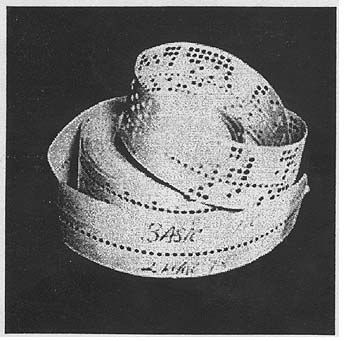

- Altair BASIC Paper Tape (1976)

Accession Number: X507.84

Gift of Bill Gates. This paper tape contains the first version of a BASIC language interpreter written

by Bill Gates and Paul Allen for the MITS Altair 8800 computer while both

were students at Harvard University. The Altair was a computer kit that appeared

as the cover story of the January 1975 issue of Popular Electronics magazine.

The BASIC interpreter allowed Altair owners to program their machines using

English-like commands. Altair BASIC was the first mass-produced commercial

program written by Gates's company, known at the time as "Micro Soft."

This paper tape contains the first version of a BASIC language interpreter written

by Bill Gates and Paul Allen for the MITS Altair 8800 computer while both

were students at Harvard University. The Altair was a computer kit that appeared

as the cover story of the January 1975 issue of Popular Electronics magazine.

The BASIC interpreter allowed Altair owners to program their machines using

English-like commands. Altair BASIC was the first mass-produced commercial

program written by Gates's company, known at the time as "Micro Soft."

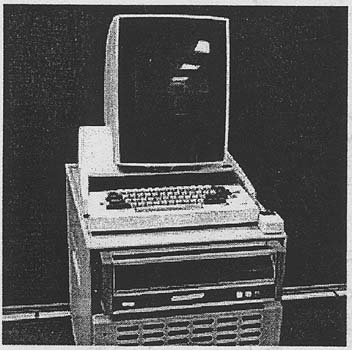

- Xerox PARC Alto (1972)

Accession Number: 1740.1999

Gift of Cliff Purkiser. In 1972 Xerox began work on the Alto desktop computer which prototyped the

graphical user interface that we all use today. It was based on a special monitor

that could display an 8'/2 x 11 sheet of "paper." Unlike terminals of the day, it

used proportionally-spaced characters that looked like they had been typeset.

The Alto had a mouse (invented earlier by Doug Engelbart at SRI in 1965), and

the now-familiar desktop environment of icons, folders, and

documents. In today's terms, it was like a Mac or Windows-based PC, but in

1975, before there were any personal computers, and on a machine with only 128K

bytes of memory.

In 1972 Xerox began work on the Alto desktop computer which prototyped the

graphical user interface that we all use today. It was based on a special monitor

that could display an 8'/2 x 11 sheet of "paper." Unlike terminals of the day, it

used proportionally-spaced characters that looked like they had been typeset.

The Alto had a mouse (invented earlier by Doug Engelbart at SRI in 1965), and

the now-familiar desktop environment of icons, folders, and

documents. In today's terms, it was like a Mac or Windows-based PC, but in

1975, before there were any personal computers, and on a machine with only 128K

bytes of memory.

- As part of that project they also invented Ethernet networking to connect Altos together building a distributed system that shared information and resources like printers. There were 150 Altos at PARC, making it the most advanced personal computer lab in the world.

- In 1981, Xerox commercialized successors to the Alto as the "Star 8010 workstation" but the machine failed, largely due to a high purchase price.

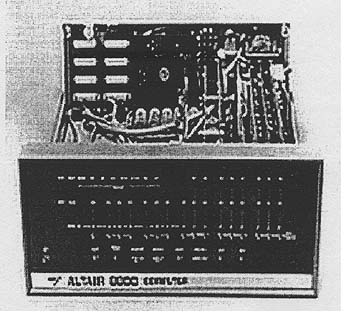

- MITS Altair 8800 (1976)

Accession Number: X1827.2000

Gift of Craig Payne. The Altair 8800 is commonly thought of as the

first successful "personal computer" or "PC."

Albuquerque, New Mexico company MITS built calculators and terminal systems throughout

the early 1970s, but, says company founder Ed Roberts, "when we found out about the Intel

8080 in late 1973, we started design on the Altair, which was finished in the summer of

1974." Initially, programs had to be entered a line at a time with the switches on the front

panel. Soon, MITS and other manufacturers were offering expansion memory boards, and

the 4K BASIC interpreter written by Bill Gates and Paul Allen [Item 5, above]

became a standard.

The Altair 8800 is commonly thought of as the

first successful "personal computer" or "PC."

Albuquerque, New Mexico company MITS built calculators and terminal systems throughout

the early 1970s, but, says company founder Ed Roberts, "when we found out about the Intel

8080 in late 1973, we started design on the Altair, which was finished in the summer of

1974." Initially, programs had to be entered a line at a time with the switches on the front

panel. Soon, MITS and other manufacturers were offering expansion memory boards, and

the 4K BASIC interpreter written by Bill Gates and Paul Allen [Item 5, above]

became a standard.

- The demand for the $395.00 machine exceeded MITS' wildest expectations. More machines were sold in the first day (through a Popular Electronics cover story) than the company expected to sell during the entire lifetime of the product. Roberts points out that the Altair increased the installed base of computers in the world by 1 % each month during 1975-76. The company was eventually superceded by other, more powerful and flexible computers, in particular a triumvirate of mass-produced, consumer-friendly machines: the Apple II, Commodore PET, and Tandy/Radio Shack TRS-80.

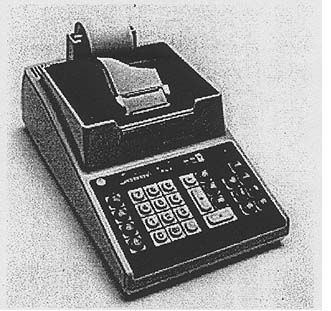

- BUSICOM Calculator (1971)

Accession Number: X1320.97

Gift of Federico Faggin. This calculator is the first device in the world to use a microprocessor and the

device for which the world's first microprocessor was designed. Four Intel

engineers-Ted Hoff, Federico Faggin, Stan Mazor, and Matsatoshi Shima-

designed and built the "Intel 4004" central processing unit (CPU) to replace dozens

of discrete logic circuits and thus meet the rigorous packaging requirements of their

Japanese customer, BUSICOM.

This calculator is the first device in the world to use a microprocessor and the

device for which the world's first microprocessor was designed. Four Intel

engineers-Ted Hoff, Federico Faggin, Stan Mazor, and Matsatoshi Shima-

designed and built the "Intel 4004" central processing unit (CPU) to replace dozens

of discrete logic circuits and thus meet the rigorous packaging requirements of their

Japanese customer, BUSICOM.

- As market conditions in the calculator market worsened due to intense competition, BUSICOM withdrew its product and sold the rights for the 4004 microprocessor back to Intel, perhaps one of the most significant business decisions in computer history, allowing Intel to diversify into microprocessors based on this technology.

- The 4004 was the progenitor to many variants of microprocessor, such as the 8-bit 8008, as well as the 8080, 8086, 8088, and "x86" family of microprocessors, now used in hundreds of millions of Personal Computers (PCs) worldwide.

- Working in seclusion for four years, Cray introduced the Cray-1 supercomputer in 1976. Like all of Cray's machines, the Cray-1 was the fastest computer in the world at time of introduction. Speed was always Cray's prime design goal and, given large cold war defense budgets, funding was rarely an issue for typical CDC/Cray customers. The Cray-1's unique physical design earned it the title of "the world's most expensive loveseat," a reference to the concentric bench that surrounds the main tower.

The classic IBM "THINK" sign was said to be a permanent feature of IBM

offices around the world until the 1970s. The "THINK" concept as company

mantra originated with IBM founder Thomas J. Watson Sr. in the 1940s and

was often parodied outside of IBM (in the pages of Datamation, for example)

when this high standard went occasionally unmet.

The classic IBM "THINK" sign was said to be a permanent feature of IBM

offices around the world until the 1970s. The "THINK" concept as company

mantra originated with IBM founder Thomas J. Watson Sr. in the 1940s and

was often parodied outside of IBM (in the pages of Datamation, for example)

when this high standard went occasionally unmet.

The 1880 U.S. census used 1500 clerks to produce 21,000 pages in seven years.

There seemed little likelihood therefore that the 1890 census would thus be

completed on time before the next census would begin. The U.S. Bureau of the

Census established a competition for better technology and a young engineer

named Herman Hollerith won the competition.

The 1880 U.S. census used 1500 clerks to produce 21,000 pages in seven years.

There seemed little likelihood therefore that the 1890 census would thus be

completed on time before the next census would begin. The U.S. Bureau of the

Census established a competition for better technology and a young engineer

named Herman Hollerith won the competition.